Masthead Feature: The Last Supper - A Queer Feast Through the Ages

Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” isn’t just a painting—it’s a centuries-long remix of faith, queerness, and radical community.

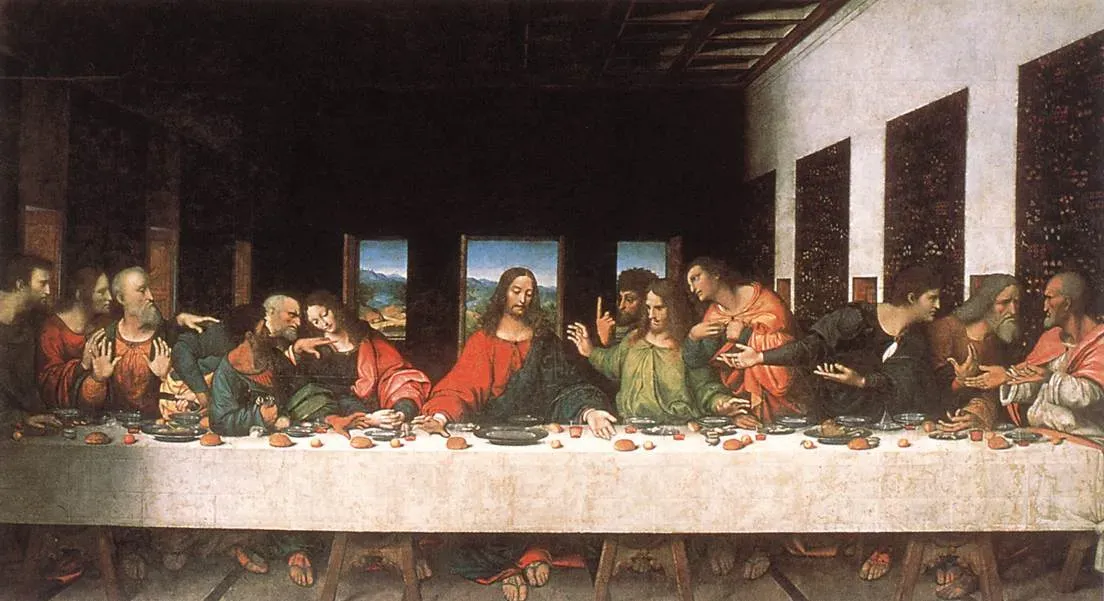

Christianity often imagines itself as the faith of heterosexuality, but when it comes to the most iconic image of Jesus, the world turns to a queer artist: Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo, a profound theologian but not a Christian, painted Jesus without a halo—just a human, at a messy, real meal. The table is alive with confusion and secrets, with a serene, knowing God at the center.

The androgyny is unmistakable. Leonardo’s Jesus is half-man, half-woman—a style that was his signature. His early sketches of Christ were even more ambiguous, a blond being neither male nor female. For Leonardo, Jesus was always queer.

Over time, the painting itself faded, becoming a ghostly vision—half in this world, half in another. Yet, it’s this image, made by a queer artist, that Christianity chose as its signature Jesus.

The “Last Supper” has become a stage for artists to remix, revise, and make their own. Frida Kahlo reimagined it as a savage, personal drama. Salvador Dalí turned it into a mystical, New Age fantasy. Andy Warhol’s 1980s variations, painted during the AIDS crisis, became a plea for salvation and a confession of the conflict between faith and sexuality.

Elisabeth Ohlson Wallin’s “Ecce Homo” depicted Jesus in high heels, sparking protests. Israeli photographer Adi Nes used the scene to explore queer identity and war. Argentine photographer Marcos López staged it as an Argentine barbecue, and Renee Cox’s “Yo Mama’s Last Supper” made Jesus a nude Black woman, igniting controversy and conversation about race, gender, and belonging.

Other artists like Zeng Fangzhi, Matteo Trisolini, Sasha Kazantsev, David LaChapelle, and Alfred Hrdlicka have also contributed powerful reinterpretations, exploring culture, identity, and community.

The “Last Supper” has inspired drag queen performances by Angelo di-Benedetto, lesbian reinterpretations by Bronwyn Lundberg, and queer visions by Douglas Blanchard, among many others.

In the end, Leonardo’s “Last Supper” is about seeing people together—even when it seems like they shouldn’t be. It’s a celebration of difference, a challenge to tradition, and a reminder that nobody owns the story of Jesus. It’s available to everyone.

Source: Leonardo’s ‘The Last Supper’ Started Out Queer and Got Queerer